By Abrita Kuthumi - WACNH Intern

August 30, 2021 marks an important day in foreign affairs history as the twenty year occupation of the United States in Afghanistan officially came to a close. Approximately 116,700 people- among them, U.S. troops, U.S. civilians, Special Immigrant Visa holders, and foreign nationals- were evacuated in the mission, according to The Washington Post. As the number of airlifts dwindled and ceased, months after the withdrawal, the focus shifted away from Afghanistan. However, the Afghanistan war cannot be easily forgotten because of the tremendous human and financial cost over the two decades: the accumulated death toll has been estimated to be above 117,587 and $145 billion dollars was invested to rebuild and stabilize the region. Beyond this data, there are countless people affected by the conflict. At all this expense, what have we learned from the Afghanistan war?

Until the Special Inspector General For Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) report was published, many internal details of what preceded the chaotic exit were unknown to the larger public. SIGAR, an independent oversight program, which conducted inspections and investigations for Afghanistan reconstruction efforts, published a 140-page report in August 2021 which highlighted key lessons to take away for the future. The full report can be found here. Although the document briefly outlines the positive outcomes of U.S. programs, such as an increase in literacy levels, decrease in child mortality rate, and doubling of the gross domestic products, the report mostly delves into details of what went wrong and suggests what policies could be adopted to improve responses in the future. Since the report’s release, some policy reforms have taken shape, such as the first policy outlined below. However, policy reforms two and three take a longer time, as they deal with complex, internal work required by governmental agencies.

Policy #1: Congress should maintain or increase the budget of the State Department to help develop and implement a stabilization strategy with the support of the United States Agency for International Development.

The State Department is the agency with the authority to spearhead overarching strategies abroad. However, given the budget of the State Department, which was (and still is) meager in comparison to the Department of Defense, there is a discrepancy between what is demanded and what can be realistically achieved. Foreign relations ought to be conducted through diplomacy rather than military, or hard power. However, since the Department of State’s budget has often ranged within the fifty billion dollars mark prior to 2021, there was a constraint on their efforts given the lack of resources. The State Department did not have the investment dollars which would allow the agency to take leadership and partner with other agencies, such as The United States Agency for International Development, to accomplish developmental goals. Whereas, the Department of Defense has always benefited from a much larger share of the national funding, often taking up 11 percent of the overall national budget, as reported by Peter G Peterson Foundation. In the fiscal year of 2020, the Department of Defense was able to spend $690 billion dollars. Provided the Department of Defense had the capacity, the agency naturally led the mission in Afghanistan instead. Since policy recommendations of expanding the budget of the State Department have been echoed over the years, there has been a sharp improvement since 2021, as demonstrated in Table I below. In fiscal year 2021, the funding reached $71.58 billion. However, this is only the beginning of building better diplomatic relations. In order to accomplish significant tasks, the US governmental agencies require assuming distinct responsibilities and filling the gap of each other. The table below demonstrates the responsibilities and gaps outlined in the report.

|

U.S. government agencies

|

Department of State

|

Department of Defense

|

U.S. Agency for International Development

|

National Security Council

|

|

Responsibility

|

To spearhead reconstruction efforts

|

To follow the lead of State

|

To oversee spending of programs

|

To develop national security policy

|

|

Gaps

|

Lack of expertise and resources; Funded Coordinator for Reconstruction and Stabilization (CRS) organization but failed to achieve tangible goals; accountability standards were stringent compared to DOD; understaffing

|

Lack of economic, policy, diplomacy, and development governance understanding

|

Lack of resources or expertise; accountability standards were stringent compared to DOD; Actions could be overruled by the National Security Council, ex: Ring Road project at the expense of agricultural and governance programming

|

Lack of process to oversee large scale reconstruction efforts

|

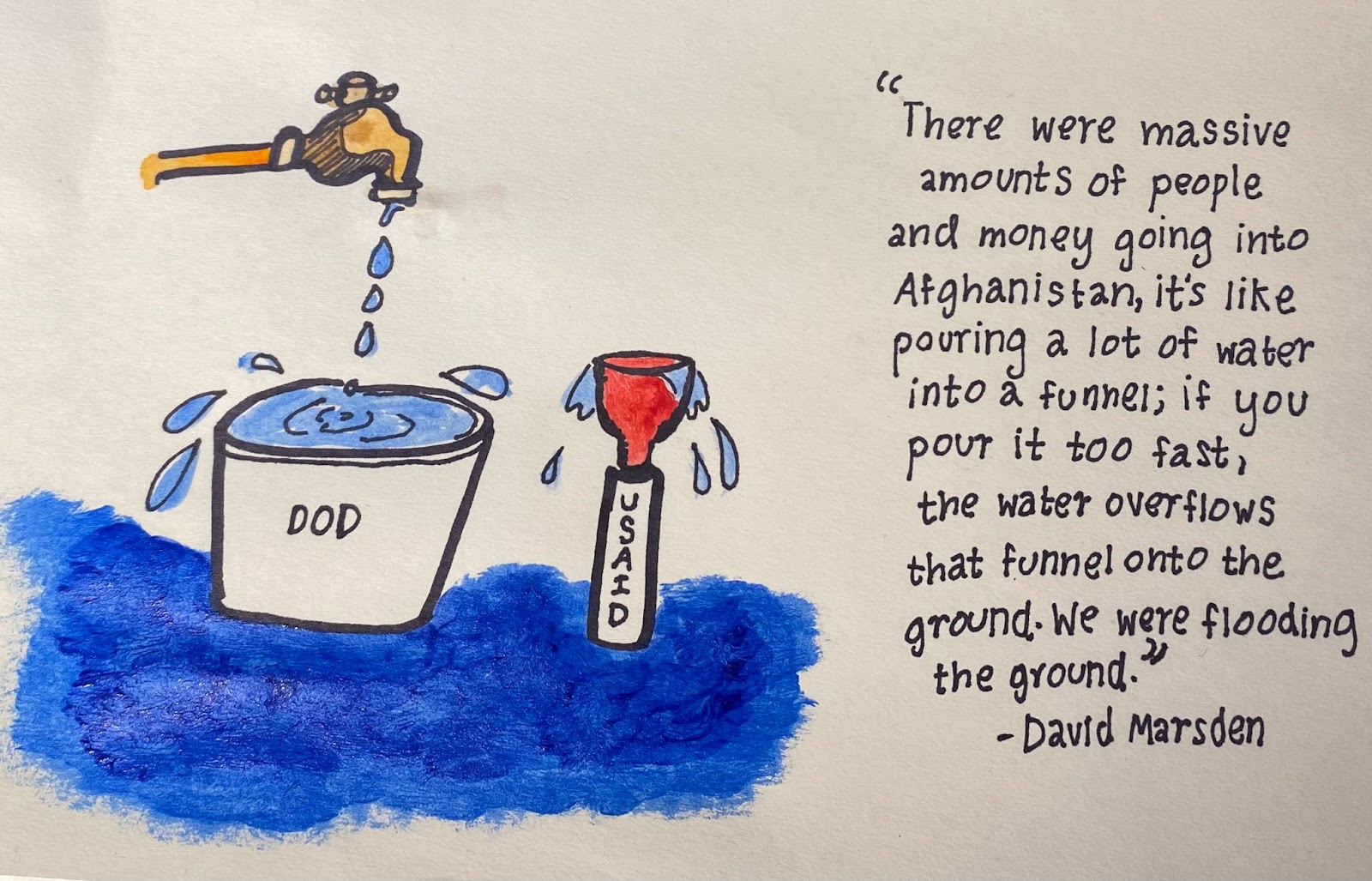

Policy #2: The U.S. government should create due dates- not deadlines- based on the conditions on the ground and prioritize spending efficiently rather than quickly.

Due to the political pressure faced by top officials within the government, programs that ran on the ground in Afghanistan also felt the rush to demonstrate quick and visible achievements. Top-down deadlines were created within offices without the consideration for how projects would be realistically achieved. As one of the most well-respected development economist, William Easterly, explained in “The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good,” if planning and aid from Western nations was all it took for development, then there would be no global poverty. Planning rigorously is not enough; progress requires understanding the local context, which then requires flexibility in timelines. If not, programs are not sustainable for the long run. Perhaps, the most toxic element of all, the marker of success and progress was measured by how much money was spent and not by what was achieved. Money can be spent recklessly and therefore, solely relying on this metric is quite misleading. The investigators concluded that this element increased corruption and reduced the effectiveness of programs.

U.S. government strict top-to-bottom deadlines

⇩

Prioritized spending quickly for short-term solution

⇩

Increased corruption and decreased effectiveness of program

The example of the G222 planes is demonstrative of how money spent did not directly correspond to progress made. In 2008, the Department of Defense approved $549 million to provide the Afghan Air Force with G222 military transport planes. In 2014, six years later, the Department of Defense could not maintain the vehicle and sold the planes, which became useful only as scrap metal, worth merely $40,257. This is only the tip of the iceberg. Many billions of infrastructural investments, which are more tangible displays of progress, in Afghanistan were abandoned, destroyed, or unused after the completion of the project, according to the report (See chart below; created by author).

Policy #3: The U.S. government must understand the Afghan context and tailor its diplomatic and development efforts accordingly.

The third policy recommendation tackles an old problem in the US foreign policy efforts. Without understanding the local cultural context, the United States projects have attempted to establish entire new systems in a place that the Afghan people are unfamiliar with. Prior to the United States’s push on formal rule of law, 80- 90 percent of disputes in Afghanistan had been traditionally dealt with through informal means. Sure, from an American perspective, the formal rule of law provides stability and equality. However, these values can be encouraged but should not be imposed on a different society with different cultures. Beyond the sociocultural barriers, the geographical context is also important to understand. Afghanistan is a mountainous country with rigid terrains. The American school buildings and infrastructure models, which seemed to be the core focus of projects, could not be easily duplicated.

Although the SIGAR report provided many different policy recommendations, the three policies mentioned above were the top priorities that stood out as necessary to be emphasized for the future. Without the State Department initiatives on diplomacy, a more comprehensive measure of assessing the progress made by programs, and geographical and socio-cultural solutions that are catered to the region, these costly mistakes are bound to repeat. While the State Department's increased budget will likely help expand their capacity for the future, the reforms for the other two issues need more time for further evaluation.